Aggression, Reactivity, and Arousal: Decoding Canine Behavior

In this post, we will deconstruct aggression, reactivity, and arousal in dog behavior. A lot is coming fast, so buckle up!

This post contains affiliate links. These won’t cost you anything, but the commissions we may earn through them help offset the cost of dog treats. Thanks for your support!

I won’t delve into specific training techniques in this presentation because it would significantly bloat the duration. Moreover, I can only confidently speak about the techniques I utilize in my own system. However, it’s important to note that there are numerous effective approaches to achieving the same goals. Many skilled trainers employ different but equally valuable methods within their systems. Presenting my approach as the sole method for achieving success would be unfair.

Now, there’s a lot to cover, so let’s get to it.

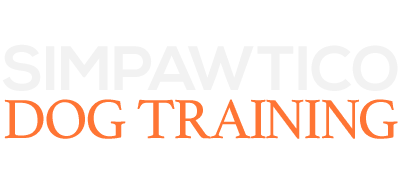

FIRST: UNDERSTANDING NEUROCEPTION

To start making sense of what’s going on in your dog’s head, we have to first talk about the concept of neuroception.

Neuroception is how individuals decode information from their senses. These sensory inputs are essentially raw data, and the brain must make sense of this information. Neuroception determines how an individual perceives and responds to their environment. It is critical in shaping our experiences and interactions; importantly—it’s completely involuntary.

Neuroception is like the brain’s built-in radar for spotting risks, helping us stay safe and survive. But sometimes, the brain can be a bit overprotective and detect risks even in perfectly safe situations.

So, while something in the environment may not pose an actual threat, it effectively becomes one if the brain perceives it as a threat. This phenomenon is related to how humans experience conditions like PTSD or anxiety.

Now that we’ve got an idea of what Neuroception is, how does that figure into Aggression?

NEXT: WHAT IS AGGRESSION?

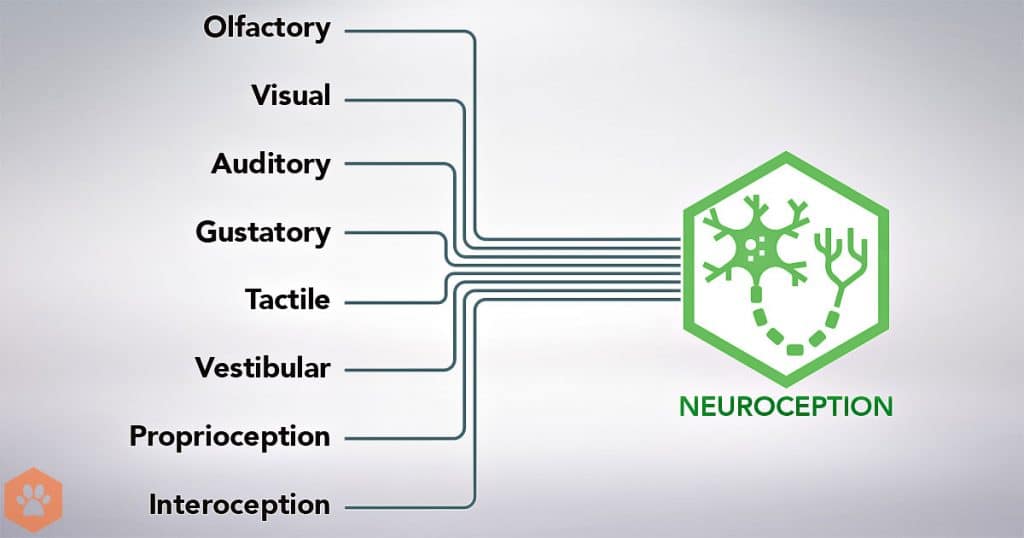

Aggression refers to hostile and threatening behavior towards a perceived environmental threat. It is crucial to emphasize the word “perceived,” highlighting the subjective nature of the threat perception. Noting this distinction is paramount in understanding the complexities of aggression.

It is crucial to remember that the primary objective of dog aggression is to create a greater social distance between the individual and the target. This is usually achieved by making the target go away (a “fight” response). Sometimes, it may mean the aggressor moves away (a “flight” response). Not all flight responses are coupled with aggressive action, but both fight and flight are part of a sympathetic nervous response, which we’ll go into more detail with later.

In essence, aggression establishes and maintains distance between the aggressor and a target.

Various forms of aggression can manifest in different ways.

TERRITORIAL AGGRESSION

One of the most prevalent behaviors in dogs is territorial aggression, which occurs when they protect their physical space. If there are any perceived threats to their territory, they will “forcibly eject” those individuals from their environment.

This behavior is inherent to all living creatures with a nervous system, serving as a vital survival technique. From gorillas and orcas to humans, wolves, and bears, territorial instincts are deeply ingrained.

Various dogs, such as Guardian breeds, have been intentionally bred for territorial aggression; we have selectively enhanced it through breeding. This attribute gives them a heightened sense of responsibility over a designated area, prompting them to take action against anything that doesn’t belong.

PROTECTIVE AGGRESSION

Protective aggression, distinct from territorial behavior, can extend beyond defending physical space. It may encompass safeguarding family members, including offspring or companions. When perceiving a threat against their loved ones, animals may resort to aggressive behavior to create social distance, ensuring their safety.

This trait is commonly seen in herding dogs, for instance, whose focus is on a group rather than a territory.

FEAR AGGRESSION

Fear aggression attempts to increase social distance as individuals become afraid of potential triggers; it is is not necessarily linked to territoriality or protectiveness but stems from the animal’s personal fear of certain environmental stimuli.

The perceived outcomes they anticipate from that particular trigger do not necessarily have to be understandable to us. Similar to someone experiencing anxiety, it may not always be logical to an outsider, yet to that individual—or dog—the neuroception is that it represents a hazard to their well-being.

RESOURCE GUARDING

Resource guarding also aims to increase social distance. It can manifest in various ways, such as guarding food, possessions, or even relationships. For example, due to their breeding and strong attachments, toy breeds often exhibit intense protective behavior towards their owners. However, their intention is not to protect their owners from harm but to guard the relationship. This behavior is often rooted in their anxious attachment to their person.

In fact, most resource guarding in the home stems from some level of insecurity. Incidentally, rescue dogs can sometimes develop a similar kind of anxious attachment and guard their new owners, new possessions, or food since these dogs have yet to develop a sense of permanence and stability in their lives. Thus, all the creature comforts we might take for granted are stupendously valuable to that dog.

You may sometimes also see a spike in resource guarding from your dog when you bring a new dog or cat into the home since the perceived value of the existing resources has now changed.

In any event, resource guarding is a natural survival instinct. Animals have relied on it for millions of years to protect vital, scarce resources. However, as we will discuss later, these dynamics can get distorted in captivity—like in your home.

PAIN-MEDIATED AGGRESSION

Pain-mediated aggression happens when a dog feels pain and reacts aggressively as a defense mechanism. Like all types of aggression, they try to increase social distance to mitigate their discomfort, to keep themselves safe if they feel vulnerable, or to alleviate their fear of impending discomfort.As an instructor for pet CPR and First-Aid, I tell students in my classes, “Any animal that is in pain or will be moved into pain can and will bite, including your own.”

Anything causing discomfort can trigger this response. Sometimes, it’s external, like a cut, a hurt paw, or even mats in their fur. Other times it’s less obvious, like internal joint pain or something in their GI tract. Dogs can even become increasingly more sensitive due to the anticipation of pain or discomfort, which is why they get defensive at the vet and the groomers or when you try to clip their nails at home.

Pain-mediated aggression is something training can sometimes help with, but primarily, you have to resolve the underlying wellness component before training can be effective.

OFFENSIVE AGGRESSION

Lastly, there is offensive aggression, which indicates a distorted manifestation of aggression. Unlike other types of aggression, offensive aggression is “idiopathic,” meaning it lacks a clear, direct motive. It tends to morph into a dysfunctional hair-trigger response to environmental stimuli. In such instances, a dog may feel overwhelmed, like they’re saying, “I cannot deal right now, and everyone needs to back off!”

This is just a basic rundown of aggression types, and each of these could be further broken down into more nuanced distinctions. For the purposes of this video, though, I think you get the idea.

RITUALIZED AGGRESSION

I would also like to mention the concept of ritualized aggression, which plays a crucial role in understanding dog behavior. Ritualized aggression is a social dynamic characterized by posturing, signaling, and exaggerated displays of aggression, all without actual conflict. This dynamic holds particular significance for canines, as engaging in physical conflict can be costly for their survival.

There are various forms of signaling, such as baring teeth, ear and eye appearance, tail carriage, and more. Piloerection and vocalization are also means of communication that indicate to another animal or person that they are agitating that dog.

I must clarify that in nature, certain animals’ behavior inherently includes physical conflict. For instance, silverback gorillas engage in fierce battles, while other species fight over mates or strive for dominance within hunting groups. Similar behaviors can be observed among certain aquatic creatures, reptiles, and birds. Physical conflict is an inherent part of these animals’ behavioral ethograms.

For canines, though, engaging in physical conflict poses a significant survival risk. Engaging in a physical fight over resources can result in injuries that hinder their ability to survive in the long run. Losing an eye, injuring a leg, or facing other impairments can undermine their hunting, foraging, reproduction, group dynamics, and overall well-being. So, ritualized aggression is a crucial stage where they communicate, “Things are getting tense. I’d rather not fight, but I will throw these hands if I have to.” Ideally, this signaling allows for resolution without resorting to actual combat.

Certain ritualistic traits have been selectively bred and exaggerated in specific breeds. Let’s focus on guardian dogs as an example. Their role is not to engage in unnecessary fights but to establish a boundary and signal to potential intruders they should stay away. Therefore, Guardian dogs have highly ritualized behavior patterns, which include a lot of growling, showing teeth, posturing, and other scary-looking behaviors. These signals indicate that they are uncertain about the presence of the individual but do not necessarily want a physical confrontation. As long as it goes away, there’s no need to escalate.

Herding dogs are also generally highly ritualized. They’re trying to motivate the animals they’re herding rather than inflict harm on them.

Here we have a dog exhibiting a display of ritualized aggression. Despite being behind a barrier, he communicates his boundaries through his ears, eyes, and facial muscles, displaying a clear warning. He would much prefer you just go away instead of having to escalate and make you go away.

LEARN TO LOVE THE GROWL

In general, most dogs will naturally display ritualized aggression before resorting to actual physical confrontation. Consequently, any skilled trainer appreciates ritualized aggression because it functions as a clear signal that the dog is agitated. It’s like an early warning system.

There’s this popular saying among consultants who work with aggressive dogs: “Never punish a growl; learn to love growling.” And you know why? Because it gives us valuable information to really understand and address the dog’s emotional state before things get out of hand.

Unfortunately, many harsh or aversive methods merely suppress the ritualized aggression while failing to address the underlying emotional content that drives aggressive behavior in the first place. That’s just superficial problem-solving. Consequently, these dogs may just stop warning everyone before they attack because they’re being forced to bottle it up. Those are the scariest kinds of dogs.

In any event, It is important to understand that aggressive behaviors in dogs have a fundamental basis in ethological survival. These behaviors are a natural part of survival and do not inherently make dogs bad. However, issues arise when captivity significantly alters these natural behaviors in unnatural ways.

Let’s look at how captivity alters behavior.

FLAWED WOLF STUDIES

The study of wolves is one of the most significant and classic examples that relates to dogs. However, it’s essential to acknowledge some gross misconceptions formed during the original wolf studies in the 1940’s. These beliefs shaped our early understanding of wolf and dog behavior. They involved concepts like alpha dominance, conflict for pecking order, and priority access to resources.

Shortly after publishing their findings, the researchers quickly retracted their statements. The researchers admitted their mistake, attributing it to the fact that the observed behaviors of those wolf packs were in captivity, in an unnatural environment where they were forced into close proximity. Once the researchers began observing wolf packs in their natural habitats, they did not witness any previously described behaviors. In the wild, wolves coexist peacefully and maintain a balance that was absent in their captive habitats.

So, captivity creates an artificial lensing effect on behavior.

It’s important to avoid directly linking wolf behavior to dog behavior, as that can cause problems. Our understanding of this topic has come a long way in the last 80+ years. While studying wolves is still relevant, it’s crucial to approach it cautiously and acknowledge our progress in this field. Remember, dogs are not wolves.

The main problem is that a big chunk of the training community still hasn’t gotten that memo from 80 years ago, you know?

DOGS AREN’T WOLVES

For one thing, dogs are captive animals, fully domesticated without any wild counterparts. Since they are 100% domesticated, they live in human homes that were not designed for them. This creates a collision, a discrepancy between their instincts’ expectations and their environment’s actual layout. So, the software guiding them may not always align with the realities they face.

Dysfunctional expressions of aggressive behaviors arise when they fail to serve our purposes or occur in inappropriate situations. However, from the dog’s perspective—in their neuroception— these conditions still trigger a valid response. This poses challenges for dogs to navigate.

If you want to learn more, I highly recommend the book Dominance in Dogs: Fact or Fiction by Barry Eaton. It’s a quick read that references all of those old wolf studies as well as lots of contemporary dog behavior research. Also, here is a video by David Mech—the main wolf researcher who coined the term “Alpha”—on why that term is outdated and inappropriate.

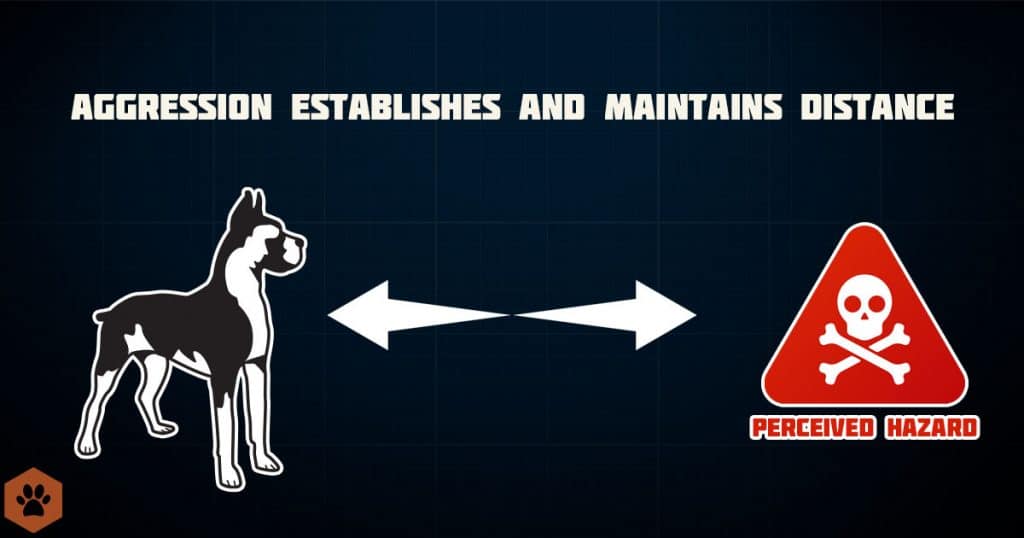

WHAT IS REACTIVITY?

Now that we’ve got the basics of aggression down, let’s dive into reactivity.

Reactivity, basically, is when you react too intensely to things happening around you. It’s like having a response that’s way bigger than what’s actually called for.

It’s worth noting that reactive behaviors are commonly driven by a desire to reduce social distance. Remember that aggression attempts to increase social distance. On the other hand, reactivity typically stems from a desire to decrease that social distance.

These dogs are all about wanting to interact with things in their environment. It’s not always the healthiest impulse, but they just can’t help themselves. It could be another dog, a person, a skateboard, or anything that’s interesting or provocative to them in their world.

So, reactivity is typically when a dog has a desire to engage with the environment and either can’t or doesn’t know how to handle themselves when they do. With enough intensity and repetition of conditions, reactivity can bubble over into aggression. Now, instead of wanting to interact, they just want to burn it down.

So, the thing is, it all comes down to neuroception and arousal. As the dog’s arousal creeps up because of their oversensitivity, their neuroception will start reading the situation as a hazard. In a second, we’ll get into the nitty-gritty of what arousal really means, but remember, this all boils down to arousal being the core of the problem.

WHAT IS AROUSAL?

I think it’s time to ensure that we have a complete understanding of arousal, too.

“Arousal” is a term loosely thrown around in dog training, encompassing a wide range of concepts. For our discussion today, it is crucial to establish a clear and concise definition of what arousal truly entails.

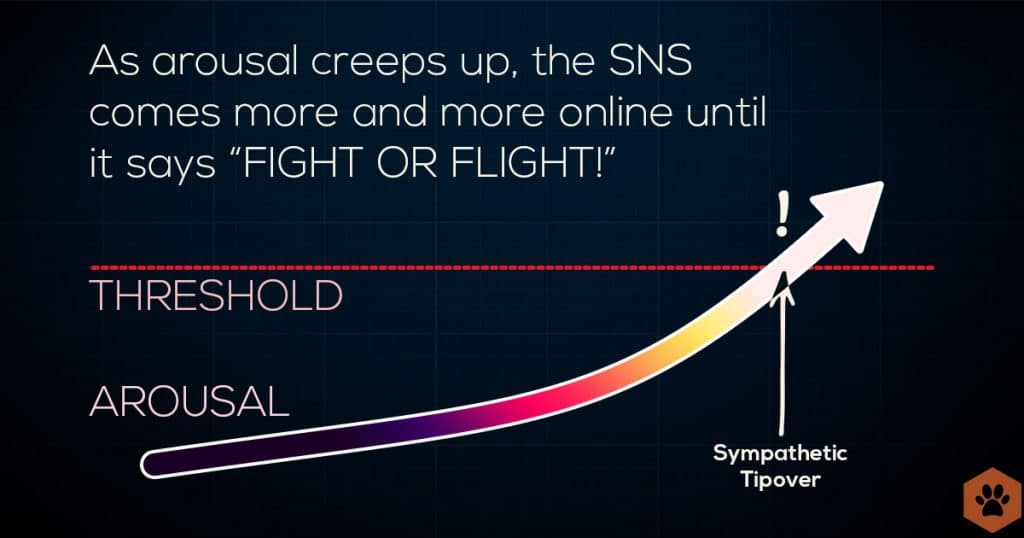

Arousal refers to a level of excitement or stimulation laced with stress. Arousal is a gradual progression toward greater activation of the sympathetic nervous system. The more arousal creeps up, the closer we get to a fight-or-flight condition.

THE SYMPATHETIC NERVOUS SYSTEM

In case you’re unfamiliar, the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) is often called the “fight-or-flight” system. It’s a primal circuit residing in the Vagus nerve. This primitive part of our nervous system excels at identifying threats in our surroundings and making split-second decisions: do I confront the threat head-on, or do I get the hell outta Dodge?

The sympathetic nervous system is not a digital system; that is to say, it’s not on or off; it’s an analog system, meaning that it’s on a fader, it’s on a dial. It works in a flexible way, allowing for a more nuanced and adaptable response.

POLYVAGAL THEORY

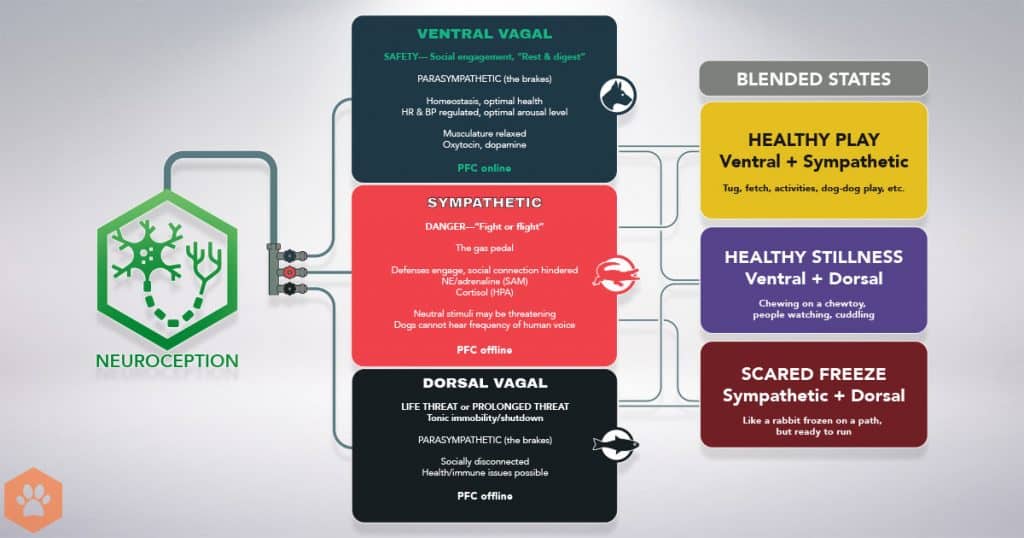

We often refer to the polyvagal theory when we delve into the relationship between the nervous system and behavior. This theory focuses on three primary components of the vagus nerve, which is connected by the cranial nerves to relevant components of the brain.

The first strand is the ventral vagal, responsible for social engagement, rest, and repair. It encompasses feelings of safety and connection.

Of course, the one we just discussed is your sympathetic, which is your fight or flight.

And then your dorsal vagal, which is stillness and shutdown. The dorsal vagal is your oldest evolutionary circuit. This activates when stress is too intense or goes on too long.

BLENDED STATES

Blended states can also occur. For example, play combines the ventral and sympathetic systems. The sympathetic system provides just enough energy to fuel the play, creating a lively and engaging experience. When you see kids playing tag or adults having a pickup game, everyone’s ventral system is activated, creating a sense of safety and social connection with teammates, family, and friends. We also see this when our dogs play tug with us or wrestle with their buddies. Although there may not be an actual threat, the sympathetic system adds a touch of energy, like stepping on a gas pedal.

On a side note: Play is seriously the Master Key to dealing with reactivity and aggression. If your training feels like play, you’ll make a huge difference in toning and tuning up the nervous system.

Additionally, there are other blended states to consider. When the ventral and dorsal systems work together, a sense of content stillness is achieved, like when you’re engaging in hobbies, or drawing, or when little kids are coloring. You see this when your dogs are settled down with a chew toy, for example.

On the other hand, when the sympathetic and dorsal systems combine, it results in a freeze response, similar to how rabbits prepare to flee while their engine is still running. You’ll see this sometimes in shelter dogs or dogs at the vet office.

And then, if the system goes full dorsal, that’s complete tonic immobility—it’s full shutdown. That occurs during a significant life threat that totally overwhelms the system.

On a side note: many people misconstrue Dorsal shutdown in dogs as calmness. Just because a dog is inactive doesn’t mean they’re calm!

PLAY: THE ULTIMATE BLENDED STATE IN DOG BEHAVIOR

I want to revisit the idea of a sympathetic state, specifically when it’s blended with playfulness. Sometimes, this sympathetic state can become slightly dysregulated and start to manifest itself in different ways.

Children, with their developing nervous system, lack the fully developed regulatory systems in adults. Their neuroception, how they perceive and respond to the world, is still in flux. This is why you might see them playing just fine one moment and then suddenly start fighting the next. If you ask them what happened, they’d probably say, “I dunno, I just got mad.”

That’s a tip-over in the SNS. The dial is turned too far, flooding the system with an excess of that energy until it triggers fight-or-flight. What was playful now transforms into conflict. That’s a dysregulation in the system.

When discussing arousal, we are referring to a state where the animal is being stimulated by something in its environment. It’s like turning up a dial, gradually increasing the stimulation level. Proper self-regulation of the sympathetic nervous system is crucial, and if the individual cannot self-regulate well enough, they’ll tip over. Through training, our goal is to help dogs control themselves better by developing their skills and abilities for self-regulation.

SELF-REG EXAMPLES

Consider police or military dogs. They possess astounding self-regulation, enabling them to engage in behaviors that would typically be interpreted as aggressive. However, they maintain just the right amount of sympathetic arousal to provide the necessary energy and intensity while retaining cognitive function. This allows them to follow commands and directions; it’s why an officer or handler can effectively call them off from engaging with a suspect. They approach the situation with confidence and expertise rather than a purely instinctual fight-or-flight response. This exemplifies the extraordinary self-regulation within their sympathetic nervous system, which is crucial.

That’s also why a knee-jerk protection dog trained to be mean isn’t a good protection dog; they’re a liability because they’re all spinal cord, no brain.

Also, take EMTs, for example. When faced with a gruesome and harrowing situation that causes others to panic and lose control, veteran EMTs remain composed. They understand the urgency of the situation and swiftly go to work, knowing exactly what needs to be done. Remarkably, they are able to maintain their cognitive function, make sound decisions, and operate effectively, all while their sympathetic nervous system provides the necessary boost without tipping over into panic.

THRESHOLD

Right here is where some threads are going to come together for you.

In dog training, the term ‘threshold’ is often used to describe the state of a dog’s nervous system. Indeed, trainers always say you must “Stay under threshold,” or “Don’t let the dog go over threshold.”

When a dog is said to be “over threshold,” it means that their sympathetic nervous system has been over-activated, they’ve tipped over the limit, and they are no longer able to think. Instead, their response is purely visceral.

This is an important concept in dog training and behavior science. When a dog surpasses their threshold, it signifies that their arousal levels have escalated beyond control, resulting in an overflow of stress hormones. At this point, their system becomes overwhelmed.

Every dog is an individual and will have a unique threshold. However, this threshold can be adjusted through effective training, support, and practice.

So, then, when we’re discussing “high-arousal,” it refers to an over-activation of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) in a given situation, but they haven’t quite tipped over yet (although they’re getting close). The SNS gives their system enough juice to over-excite them, so dancing and vocalizing turns to barking and height-seeking, then grabbing your sleeves, and so on, until they either get a chance to down-regulate or pop. If you have multiple dogs, this is usually the part where a fight breaks out, just like those kids on the playground.

Dogs experiencing chronic high arousal have dysfunctional regulatory systems that consistently activate the sympathetic nervous system beyond what is necessary for that specific situation. They may not go over threshold in every situation but are likely closer to their threshold than what would be considered optimal.

INCENDIARIES

Now, let’s look at some contributing factors of arousal, reactivity, and aggression.

FRUSTRATION

Frustration plays a major role in arousal, reactivity, and aggression. Many dogs find human society puzzling and, as a result, often feel frustrated. If you really take a look at dog’s lives, they typically don’t get a lot of agency. Their lives are stupendously and excessively micromanaged. You gotta appreciate our furry friends for putting up with a lot of human B.S.

Much of that frustration comes from restrictions on their freedom of movement. When they cannot respond to pressure in the environment or close social distance if they want to, it can be neuroceived as a hazard.

Restriction of movement is typically experienced from the front or the back. For instance, it could involve being behind a dog with a leash, tether, or a back-tie. Dogs that tip over in these situations are typically called “Leash reactive” or “leash aggressive.” Likewise, if you have a dog experiencing some other type of aggression—such as territorial for example—and a leash or tether is hindering them, frustration may ramp up the intensity of their response.

On the other hand, restriction from the front may involve a barrier like a gate, fence, or kennel door. Dogs that dysregulate in these situations are typically called “Barrier reactive” or “barrier aggressive.” In shelters, this is typically called “kennel aggression,” although, as you’re learning, “aggression” may not always be an accurate label, depending on the dog and their motivations.

A fascinating video online demonstrates how restriction of movement can affect a dog’s emotional state. The video shows two dogs separated by a moveable gate. At first, they bare their teeth, but, when the gate opens, they start sniffing and giving each other curious glances. When the gate closes again, they start up again. It’s interesting how reducing or removing those frustrating elements can deflate reactive behavior.

Restrictions of movement could even include people crowding or hugging dogs that don’t want it. There are tons of videos of dogs being crowded by someone and then using aggressive behavior to create distance. Their system over-responded to the neuroception of a frustrating hazard, and then they popped and went over threshold.

PRIOR LEARNING

Another factor to consider is prior learning. This can lead to conditioned responses, where dogs gradually experience increased sympathetic activation when stressed, which can compromise their regulatory systems.

When the sympathetic nervous system is constantly activated, it can start to deteriorate, resulting in exaggerated and more frequent responses to stimuli. This ongoing activation and subsequent deterioration could potentially cause certain types of PTSD.

The same idea applies to dogs who have had traumatic experiences with other dogs, humans, or even objects in their environment. This prior learning can result in an exaggerated response to similar stimuli in the future. When they become predictable to the dog, all of those “incendiary” contributing factors will activate a faster-than-normal response in the dog’s brain and nervous system. The next time they see a dog, similar person, or similar object, they’ll skip several steps and go right to aggression.

GENETICS

Genetics also affects how sensitive a dog may be to different stimuli. This is often related to the kinds of jobs we bred dogs to do, which they rarely do anymore because they live in the suburbs or in apartment buildings.

For example, sighthounds were bred for their incredible eyesight and speed in chasing small animals. However, it’s not surprising if a greyhound that spends his life in a cul-de-sac instinctively chases a neighbor’s cat. This unintended response happens when the stimulus, like a cat running across the road, closely resembles the situations they were originally bred to respond to.

Let’s talk about guardian dogs again. Originally, they were relaxed companions on farms. They only sprang into action when they spotted human or animal intruders. However, nowadays, mastiffs and Great Pyrenees are often found lounging in living rooms instead of keeping watch on hilltops. Then, when someone unexpectedly visits, their territorial instincts inadvertently kick in. As a result, they may not always be the most welcoming.

Herding dogs were made to be sensitive to sudden changes in flock or herd behavior. Now, without that stimulus and a functional way to release it, they get amped up when people in the living room suddenly start moving.

Similarly, terriers have had steps deliberately taken out of their predatory sequence to boost their quick-to-action gameness. This allows them to carry out their original tasks of near-suicidal pest control efficiently. While this will keep the rats out of your barn, it may not work as well when strolling through the suburbs with squirrels, stray cats, and little kids running around.

This doesn’t make any of these dogs bad. If anything, it’s our fault; we created these situations! So, we have to work through it with them cooperatively, compassionately, and supportively.

Now, don’t get me wrong. None of what I’m saying is prescriptive. Every dog is an individual with their own genetics, their own life experiences, their own prior learning, and unique environment that they live in.

The impact of sympathetic system activation varies significantly among individuals. Some may exhibit heightened aggression, while others may experience panic, some become reactive as they try to engage with something, and others may have confusing mixed feelings. JUST LIKE PEOPLE! In the end, it really depends on the individual’s own traits and predispositions. It’s all relative, you know?

WHAT TO DO

How do you address reactivity and aggression with arousal as the backdrop, taking into consideration the animal’s neuroception, which is affected by their prior learning, genetics, and environment?

Wow, that’s a mouthful.

It’s important to remember that when training a dog, simply working under the threshold isn’t enough. In fact, it’s crucial to approach the threshold to create enough context for the dog to learn new strategies to cope with the stimuli. If you don’t push the limit, you’re not giving the dog the opportunity to learn and adapt. So, it’s important to tickle that edge and work at the upper limits of their threshold.

FEATHER THE EDGES

For example, I don’t want to get so far away from a trigger that the dog just sits there and looks at it. I want to get to where the dog is starting just kind of to activate a little bit. So I’m just feathering that edge. That gives the dog enough context for them to start building new branches on their decision tree. We haven’t tipped over. We haven’t gone over the threshold, but there’s still enough thinking brain online that they can start saying, “Oh, man, this thing you’re having me do feels a lot better.”

“I know, right?”

We also have tools like progressive desensitization, counter-conditioning, habituation, and training that provide functionally equivalent substitute behaviors. You should discuss these with your certified trainer, behavior consultant, or behaviorist.

AVERSIVE STIMULI

Consider another aspect: aversive stimuli may trigger reactivity. Regardless of the opinions of trainers who advocate for prong collars, e-collars, or slip leads, it is important to acknowledge that these tools inherently provoke an avoidance response driven by the sympathetic nervous system.

If there’s already dysregulation in the sympathetic nervous system, then using other tools that increase hazard avoidance is moving in the wrong direction. For these tools to work, they have be a bigger threat than whatever is in the environment.

This is especially problematic because it presupposes that the only thing that matters is what’s on the surface. It’s not a question of what the dog feels or needs. The idea is just to change what they do. It’s compulsive compliance.

If an owner hasn’t taught a dog to self-regulate properly, the dog’s whole system can start dysregulating in other ways. This can lead less experienced trainers to misuse and abuse those tools. And let’s be real, if you’re using those tools to treat high arousal, reactivity, or aggression by attempting to suppress the behaviors that you find annoying, it’s like trying to fight a house fire with a flame thrower. Not the best approach, right?

OUTCOMES

As you train your dog with knowledgeable, supportive methods, you are helping them become more resilient, confident, and stable.

As I mentioned earlier, adding play to their training routine is an awesome way to activate their sympathetic nervous system in a controlled manner. It helps them develop effective coping mechanisms by finding that sweet spot between the ventral state of safety and social engagement and the sympathetic system. This makes play a powerful tool in rehabilitation because it tunes and tones their responses, making progress with aggression, reactivity, and over-arousal happen super quickly.

In addition, it’s crucial to have a strong partnership and support from the handler. I can’t overstate how vital it is to work cooperatively with your dog to co-regulate their emotions and behavior until they can better self-regulate.

LANGUAGE MATTERS

The last thing I want to discuss with you is how language matters.

Language is important when it comes to talking about dogs (and people). Some folks tend to refer to dogs as “reactive,” “aggressive,” or “dominant.” However, these labels are useless because they tend to pathologize the dogs. It’s important to choose words that don’t label the dogs and instead focus on their behavior and what we want to change to help them.

Don’t make your dog their behavior. These are behaviors, not personality traits. They’re not trying to be a problem; they’re having a problem. Using language that helps us distinguish our dogs from their behaviors allows us to focus on the behavior itself without conflating it with the dog’s identity.

- So, instead of saying, “It’s an aggressive dog,” we can say, “It’s a dog exhibiting aggressive behaviors.”

- Similarly, instead of referring to a dog as “reactive,” we can say, “It’s a dog struggling with reactive behavior.”

- Likewise, rather than describing a dog as “high-arousal,” we can say, “It’s a dog exhibiting higher than normal levels of arousal.”

- Lastly, instead of labeling a dog as “dominant,” we can say, “It’s a dog displaying inappropriately dominant behaviors for the situation.”

“TRUE AGGRESSION”

I would also like to mention another concept called “true aggression,” which has been on my mind recently. The other day, I received an email from a woman struggling with her dog’s aggressive behavior. She reached out to us because previous trainers were unable to resolve the issue. These trainers claimed that if it was “true aggression,” the dog wouldn’t take food in certain situations or wouldn’t sit with its back turned.

The concept of “true aggression” is essentially meaningless because aggression itself is a behavior. There is no such thing as “true” or “false” aggression, as this behavior’s primary objective is to—as I said—increase social distance. So, when a dog exhibits behavior to create distance, that’s aggression.

The only thing that changes is the intensity. So, usually, what people actually mean is “severe” or “non-severe” aggression. Behavior is on a continuum. Obviously, lunging and snapping is more severe than growling.

Behavior is contextual, too. A dog that was growling five minutes ago and is now sitting next to you and taking treats just means that now their neuroception has shifted, and they feel safer. It doesn’t mean that five minutes ago, they weren’t displaying aggressive behavior.

So we need to use the correct terms in these situations because if we use these bozo terms like “aggressive dog,” “dominant dog,” “reactive dog,” or “true aggression,” then we just forestall sensible treatment because we are not looking at the underlying core mechanics.

WRAP UP

All right, everyone. We have covered an industrial dump-truck load of info. Chew on it, review it as needed, and if you have any questions, please put them below.

If you’re working through aggression, reactivity, or high arousal with your dog, look at my post on Six Strategies for Environmental Management. Those will be your first steps to getting ahead of things. As I mentioned earlier, work closely with your team of professionals, including your certified trainer, behavioral consultant or behaviorist, and your trusted vet.

As always, keep learning, keep practicing, and we’ll see you in the next one. Thanks for looking!